Dr. Elizabeth “Betty” Kutter is waiting for me at the entrance to the Lab II Building at The Evergreen State College. She greets me with one hand wrapped around her elderly dog’s leash and the other gripping a water bottle with the words “There’s A Phage for That” imprinted on it. As we walk down the hall she tells me that she moved into her lab here the day the building opened in January 1972. Kutter, who has a PhD in Molecular Biology / Bio Physics, brought a grant from the National Institute of Health with her to study phage. Kutter has been studying phage for more than 50 years.

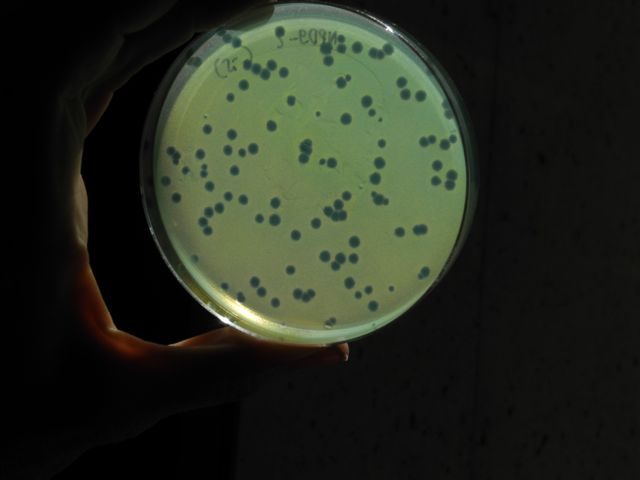

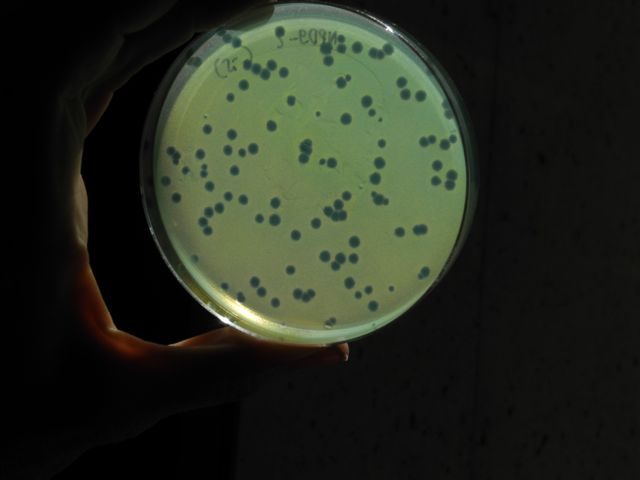

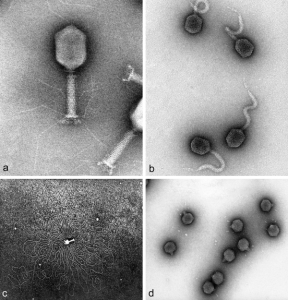

A bacteriophage, (informally, phage) is a virus that infects bacteria. The term is derived from “bacteria” and the Greek phagein “to devour.” Phages keep bacteria regulated. They are found everywhere, in the soil, water, and inside animals. “There are phage that do all sorts of things,” Kutter explains. “Any kind of bacteria in any environment will have phages. One fourth of bacteria in the ocean at any given time are infected with phage.”

A math major in college, Kutter tells me how she made the change from math to biophysics.

“At first I thought biology was for people who couldn’t do real science. Basically, I enjoyed math and was very good at it by then, but came to the conclusion that the questions being asked in molecular biology were much more interesting than those being asked in mathematics,,” she recalls.

“In 1990, I was leading a group determining the genome sequence of phage T4. Some of the scientists in the group were from the Soviet Union and I got funding to visit with them through an exchange program between their Academy of Sciences and ours. I spent four months there, mainly in Moscow, but I also visited Tbilisi, in the Republic of Georgia. Prior to that, I did not know about phages being used therapeutically. They have been used for over 90 years as an alternative to antibiotics in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, but were also used in the United States through the 1940s and in places like France, into the 1980s; a little use still continues there,” comments Kutter.

In The Republic of Georgia, phages are being used routinely as part of general health care and are licensed to be sold in the pharmacies, approved by the government’s ministry of health. The new phage batches are tested every six months in terms of efficacy and sterility. “It is a standard part of medical practice in that part of the world. They come in little 10 ml bottles which you can buy off the shelf in the pharmacy,” Kutter comments.

Most western countries ended their use and research of phage therapy in the early 1940s because antibiotics became available, worked well, and were cheap to produce. “Research and development has resurfaced however, as phage are seen as a possible therapy against drug-resistant strains of many bacteria,” says Kutter.

As a complement to antibiotics, phage therapy is currently used in a few other parts of the world and in some research situations in this country for treating diabetic ulcers, MRSA, lung infections of people with cystic fibrosis, pseudomonas, and various severe or intransigent gastro-intestinal problems.

Research is being conducted in Bogotá, Colombia to isolate a phage against a bacterial pathogen that is killing shrimp and also to find a phage that can be used to treat chicken and eggs against salmonella. Omnilytics, a company in Salt Lake City, Utah has been marketing a phage against tomato blight for a dozen years. The company also now markets a number of agricultural products.

“In the United States, the Northwest in particular, phage are being brought here as part of a research agreement,” Kutter explains. “Washington and Oregon have laws that allow naturopathic practitioners to research wisely, safely, and with efficacy, natural products approved and used extensively in other countries. Naturopaths have the depth of training and knowledge, as well as professionalism and regulation in this state to make it appropriate for them to use products like phage in therapy.”

The phage cocktails used in this therapy are produced by the Eliava Institute, located in Tbilisi, Republic of Georgia.

Kutter was on the board of the Naturopathic College in Seattle for its first 15 years of operation. She comments that The National College of Naturopathic Medicine, in Portland, Oregon, which has been in operation since 1915, has recently introduced a master’s degree in research in complementary medicine.

Kutter is internationally known for her research on phage and her interest and enthusiasm for collaboration. Now retired from teaching, her research is funded in part through contributions to the non-profit Phage Biotics Foundation, but Kutter says that she pays for the majority of lab expenses with her retirement funds.

An interesting note from Wikipedia states, “Since ancient times, reports of river waters having the ability to cure infectious diseases have been documented. In 1896, Ernest Hanbury Hankin reported that something in the waters of the Ganges and Yamyuna rivers in India had marked antibacterial action against cholera.”

As we leave her lab and walk back down the hall, Kutter talks with enthusiasm about the 20th Biennial Evergreen International Phage Meeting which is being held August 4-9 at The Evergreen State College. For information contact: tescphage@gmail.com.

Looking for more phage information?

The Phage Biotics Research Foundation is a non-profit group formed to support the research of places like the Eliava Institute of Tbilisi, Georgia through fund raising, and to promote the advancement of phage therapy around the world.

Information regarding phage biology, phage therapy, and the research studies that Dr. Betty Kutter is doing in her lab at TESC can be found on her website. You can also read more about the bacteriophage community here.

For the non-scientist, Kutter suggests the book: Viruses vs. Superbugs , available in paperback, by Thomas Hausler.